Abingdon: A town of artists, outdoor wonders and food

Visitors wander around Abingdon in spandex or their Sunday best, ready to roll a smooth 34 miles downhill on the Creeper Trail or to spend an evening mesmerized by a stage show at Barter Theatre.

Whether by chance or design, this little mountain town of 8,000, nestled in the southwest corner of the state, has become a center of Appalachian culture, with crafts and farm-to-table food, historic museums and mountain music.

People have been streaming here since before our country was a country. During the Revolutionary War, hundreds of well-armed militiamen gathered here to begin a 220-mile trudge to the Battle of Kings Mountain, a fight that Thomas Jefferson himself said turned the tide of the war.

Today, re-enactors come in costume to the Abingdon Muster Grounds to practice classic crafts and tell stories. Folks with fly rods come for trout.

The biggest attraction, though, is the Barter Theatre, which draws 165,000 a year. Founded by Robert Porterfield, a judge’s son from nearby Saltville, the theater was conceived during the Depression as a place where people could “barter ham for Hamlet,” as the theater’s director of sales, Amber Fiorini, puts it.

Porterfield had moved to New York to be an actor. When the Depression hit, he returned with a proposal. The fertile Appalachians had an abundance of food. What if he brought in a troupe of actors and stagehands, lorry drivers and playwrights, and opened a theater?

“A lot of these theater people had never been below the Mason-Dixon Line, so you can imagine what it was like to come to this rural Virginia town,” Fiorini says.

The first show sold out. The locals found a use for produce they couldn’t sell. The actors and theater staff were well fed, the locals were entertained, and the theater has thrived ever since. Patricia Neal played here, as did Ernest Borgnine, Ned Beatty and Gregory Peck.

There are stories of patrons milking cows onsite, of a man offering up a beheaded rattler that made “mighty fine vittles,” of a sow who gave birth to piglets, feeding actors for years. So much food came in that Porterfield once stood in front of the curtain and begged, “No more tomatoes!”

In the 1950s Porterfield heard that New York’s Empire Theatre, where he had performed, was going to be razed for a parking lot, so he organized a caravan of pickup trucks to salvage seats and lighting, props and costumes.

Today the sets are built in one of the theater’s 11 facilities across town, taken apart and then hoisted up through a second-floor door via a pulley system, reassembled and disassembled for two different shows a day. Below stage, costumes for Shrek hang next to those for Exit Laughing, and wigs made by hand for each performer line the walls. The costumes are sewn and then washed onsite, the wigs restyled daily. In all, the theater employs 175 people.

The lead roles rotate, so the star of one show is the unnamed cast member in another. “There is no hierarchy, there are no stars,” Fiorini says. “We are all here for the greater good of Barter, not for ourselves.”

Across the street and connected during the Civil War by a hand-pickaxed tunnel is the Martha Washington Inn and Spa. Built as a grand manse by a general from the War of 1812, it became a pricey finishing school for girls, then a Civil War hospital, then a space that housed actors from the Barter. It is now a luxury hotel. The wife of the finishing school’s headmaster was Martha Washington’s niece, so they borrowed her name as homage – and perhaps to cash in on reflected glory.

Edith Wilson, wife of Woodrow and arguably the first (unelected) female president when she quietly took over after Woodrow’s stroke, was a student here. Eleanor Roosevelt was a guest, as were presidents Harry Trumanand Jimmy Carter. The formal dining room is now a library, where guests sip their nightly port, browsing books or chatting up their fellow travelers. Out back there’s a pool under glass and a pond-shaped pair of hot tubs, plus tennis courts and pickle ball, a trampoline and tetherball for the kids. In the ballroom hang crystal chandeliers salvaged from the Empire.

Visitors then and now eat just down the street at The Tavern, with its moss-covered roof and low, wood-beamed ceilings. The martini is served in a chalice. The filet mignon is stuffed with shrimp and bacon and herbed cream cheese. The signature Tavern trout comes with toasted almonds and dill horseradish butter.

French King Louis Philippe stopped here, as did President Andrew Jackson. A good 80 percent of the furnishings are original, so it’s possible that today’s guests are gracing the same bar stools, the same chairs.

The Tavern, one of the few buildings that survived the Civil War, is now part of a 20-block stretch that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Where once it swarmed with silversmiths and weavers, tinsmiths and cabinetmakers, apprentices and enslaved people, now there are high-end clothing stores, an olive oil shop, a locally sourced restaurant called the White Birch. There you can get quinoa topped with scrambled egg, mushrooms, spinach, caramelized onion, Ziegenwald Dairy goat cheese, avocado, red pepper yogurt sauce and parsley. Add bacon, sausage or chorizo if that doesn’t sound like enough. The list on the wall will tell you who provided your beef and pork, your goat cheese and bacon, your kale and flowers and herbs.

One road over and down the hill is Wolf Hills Brewing, a converted icehouse where on warm weekend nights more than 300 people spill out onto the lawn or dance to live music on the rough concrete floor. Up a crooked set of stairs behind the bar are a pool table and dartboards. Christmas lights string across the ceiling.

Abingdon is a soft launching place, a space where you can stay and eat and browse, or venture out to see nearby wonders like the eroded limestone of the Channels Natural Areas Preserve, the wild ponies of Grayson Highlands State Park, and Hidden Valley Lake, high up at 3,500 feet.

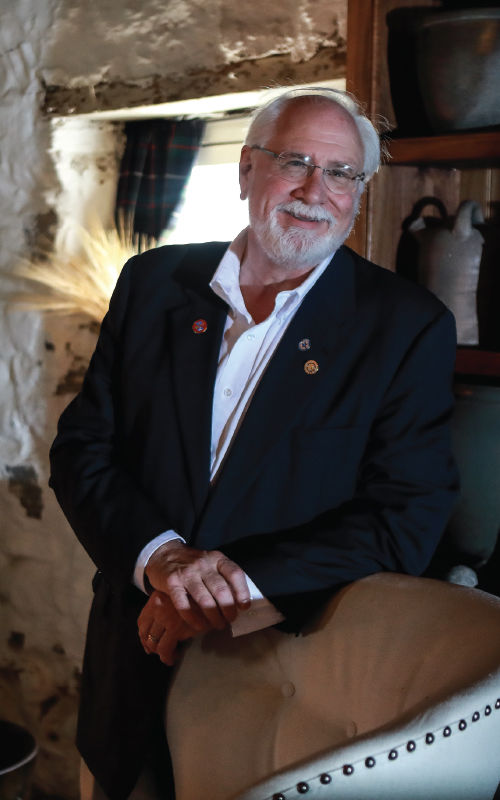

Whole parties of people come here, renting up the rooms in A Tailor’s Lodging, a restored 1840 building with a separate suite in the actual tailor’s shop out back. Owner Rick Humphreys has roots going back five generations in this town.

A collection of rifles hangs on a wall, each representing a regional style. Back in the mid-1800s the county had seven gunsmiths. “Sometimes there’d be a guy who was a good shot and his (gun) had a big patch box on it,” Humphreys said. “Everybody said, ‘I want one like that.’ ”

His sister owns Creeper’s End Lodging across the street, and sometimes reunions of cyclists will rent up both places, catch a ride from the bike shop up to the top of the Creeper Trail and roll back down to town, maybe to shop at Southern Gypsy, which offers tin chickens out front and a mishmash of treasures inside.

Nearby is Wolf Hills Antiques, with classical music cranking out over storm sound machines, and must-haves like collectible thimbles, tokens for a Denver brothel, and shadow boxes of massive tarantulas, beetles and moths.

All day the train horn sounds. At night it’s silent by city ordinance, but the train has long been a key part of what made this town a trade hub. Now the old train station is the Arts Depot, with seven working artists who welcome you in to talk about their work.

High on another hill is the William King Museum of Art. It, too, was once a school that was commandeered during the Civil War. By the 1970s pigeons flew through broken windows and rain flowed through the roof. Now it’s a climate-controlled, secure museum with three galleries, one devoted to traveling shows from all over the country, one to contemporary regional artists, and one to traditional Appalachian art – including a massive log loom that was used to turn the wool from sturdy sheep into fabrics and clothing.

This is Appalachia, so music matters. On warm Thursday nights people gather for concerts at the Abingdon Market Pavilion. In the winter they head to the Barter for Sunday jams. Over the weekend they dance and eat barbecue at Bone Fire Smokehouse & Musictorium.

Abingdon is a stop on the Crooked Road, a nine-venue music collective that delves into traditional mountain music. The Southwest Virginia Cultural Center and Marketplacehosts open jams, often on a stage that looks like a picking porch, where fiddlers and banjo players, guitarists and mouth harpists take turns on tunes that have been played in these hills and valleys for generations.

The cultural center is intended as a gateway to a community as big as Connecticut, where you can browse the work of 180 artists who work in pottery and glass, fabric and wood. The cafe’s food comes from local farms, its beverages from the region’s 15 wineries and 22 breweries.

The goal here is to emphasize the creative economy rather than the traditional economic engines of coal and tobacco. It is the artisans, musicians and chefs – and the area’s outdoor wonders – that are the bridge between the region’s Appalachian past and its sustainable future.