The Dark Spirits of Virginia

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

There is a smell and a taste to the air in a distillery, of smoke, farmer’s grain and something akin to molasses, plus the yeasty sourness of beer and the nuttiness of toasted barley, and the richness of whiskey breathing in and out of oak.

It’s a Virginia tradition, whiskey. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson made it, and sipped it on their verandas as they helped shape the New World. James Madison was known to down a pint a day, and the average colonist consumed 5 gallons of spirits a year. Lest that sound shocking, that’s about 1½ drinks a day. Not healthy, perhaps, but not enough to leave them incoherent and stumbling, either.

The magic and mystery of the making evolved long before this country was conceived, and it hasn’t changed much since. A grain is ground and soaked into a porridge-like mash that’s

blended with yeast and malted barley and left to ferment into the crudest of beers. It is then heated in a still to a sweet spot between the boiling points of alcohol and water, so the alcohol turns into a vapor that rises high above the water and solids and long-chain ethanols in the mash below, then converts to liquid form as it slides down the long, cool copper coil of the condenser, and eventually into the bottle that finds the glass.

There are distilleries in Virginia so old that a recent owner is a scant three generations removed from Robert E. Lee, and distilleries so young they’re making up new rules. Three that give tours are within a scenic road trip of Hampton Roads.

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

The old one, owned in part until 2004 by the great-granddaughter of General Lee, is A. Smith Bowman, founded in Algiers, Louisiana, and moved in 1934 to a farm that grew to 7,000 acres in what is now Reston. The whiskey was a post-Prohibition product of the excess crops Bowman grew to feed his dairy cattle. The cycle was perfect – harvest the corn, distill the whiskey, feed the spent mash to the plump and happy cows, plant more corn. The cows are important, because only 10 percent of what goes into a still comes out as consumable alcohol; the rest has to find a use.

In 1985, the third generation of Bowmans conceded to Reston’s growth and moved the operation to a Fredericksburg plant where workers once made the cellophane that wrapped the cigars and cigarettes produced in Richmond by tobacco companies that made Marlboros and Lucky Strikes. The cows stayed behind, as did the fermenting tanks and the drying operation that turned the spent mash into livestock feed.

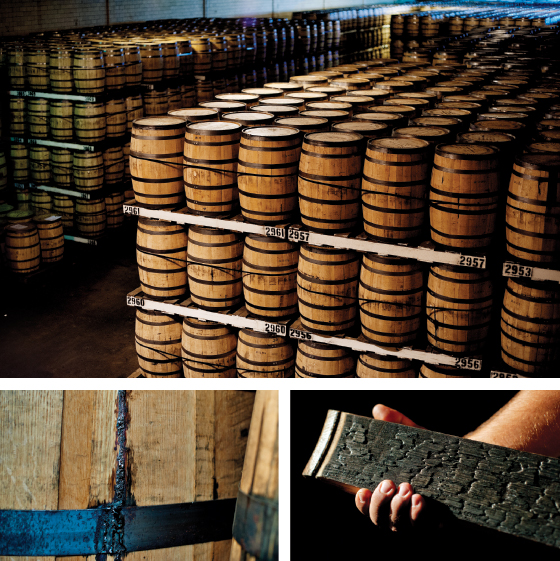

The distillery’s primary product was and is bourbon, which by law must be between 120 and 160 proof, made in America of at least 51 percent corn, and aged for at least two years in new, charred, white-oak barrels. Those are the rules for bourbon, but Virginia whiskeys are made of recipes of rye and wheat and barley, too, and they all go into barrels, sidling into the wood as it expands in summer and being squeezed back out in the winter, when the staves contract in the cold.

The aging and the charred oaking of whiskey seem to have evolved from simple happenstance. Whiskey fresh off the still can be harsh – at A. Smith Bowman’s they call it White Dog because it is clear and so strong that it bites like a dog – but when it was put into barrels and transported from town to town over rugged roads, agitated by the bumps and warmed and cooled and warmed and cooled by the weather, it became mellow. A smooth alchemy of whiskey and wood.

White oak was used because it was plentiful, pliant and porous. It was charred because the heat cauterized the sap exudate that otherwise would turn the whiskey rotten; it was just luck that the charring smoothed off the whiskey’s rough edges and gave it its amber glow.

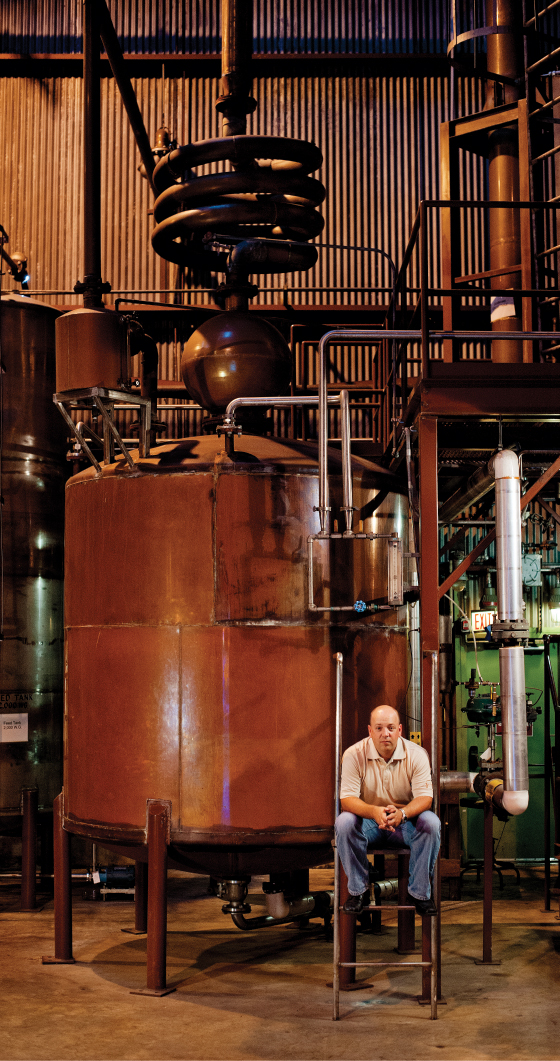

At A. Smith Bowman’s, cheerful tour guides show guests the grains and the barrels and the alligator wood of a charred stave, then present the magnificence of their still, a Lost-In-Space-style copper behemoth that looks as if it could transport mere mortals to another dimension.

The distillery is now owned by Sazerac, a privately held company based in Metairie, Louisiana, and the fermenting of the mash and its first distillations is done at one of the company’s other plants. But it’s in this giant still that the spirits are distilled a third time and then pumped with a gasoline nozzle into 120-pound barrels, their bung-hole plugs driven home with mallets of rubber or wood because anything metal might cause a spark, and 125-proof spirits are nothing if not volatile.

The barrels then join rack upon rack of others, 5,600 of them, more or less, stacked high in a soaring room, their sides weeping tarry streaks of barrel candy, a combination of water and whiskey and wood. The air is heady with evaporation – what distillers call the angels’ share.

“It has to be angels nipping,” says tour guide Mary Ahrens, “because the devils wouldn’t leave us anything.”

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

Six or eight or 12 years from now the plugs will be pulled and the barrels emptied over a grate that will catch the charred wood and let the heart of the whiskey drain down a trough to a tank, where it will be mixed with distilled water to get it down to the proof that matches the label. The best barrels will be aged 12 years and then bottled on their own to become the 100-proof, single-barrel John J. Bowman; others will be aged six or more years and then combined, no more than eight barrels together, into the 90-proof, small-batch Bowman Brothers, all of it hand-bottled on-site, along with vodka, rum and gin.

An hour and a half away, just outside Shenandoah National Park, there’s a distillery in an old apple-processing plant, across the creek and down a side road on the edge of Sperryville, a town so small its entire population could fit into your local Kroger.

A chalk sign on the porch reads “Whisky is Sunshine and Love, held together by Water.” Heavy wooden doors that mimic the staves of whiskey barrels open onto a sitting area of Oriental rugs and barrel chairs, and a store staffed by a woman who introduces herself only as Mom, although her more formal name is Helen.

Her son, Rick Wasmund, 54, the owner and master distiller here at Copper Fox, wears a T-shirt with a drawing of a glass on the front and the words “half full.” He is the kind of man who wanders a town on cool nights, seeking the scents wafting from neighbors’ chimneys. In years past, his porch was stacked with split oak and apple and cherry, woods chosen for the intensity of their heat and the smell of their smoke. He worked as a certified financial planner and dreamed of somehow combining his love of wood and of whiskey, and also of bringing his dog with him to work. When he turned 40 he toured distilleries all over the United States, the idea germinating that maybe there was a market for a whiskey infused with fruitwood. No one else was doing it, so perhaps it wouldn’t work. Or perhaps it would, and he would open up an untapped market.

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

In 2000 he went to Scotland’s tiny island of Islay for a six-week internship, his front door opening into the town and his back door into the august Bowmore Distillery, where he worked parts of all three shifts, taking notes and learning from men with a combined century of experience in the art and science of spirits. Bowmore is one of the few distilleries in the world that still malts its own barley, and Wasmund not only wanted to malt his, he also wanted to then smoke it over fruitwood to see if he could instill the joy of the wood into the whiskey.

Wasmund’s barley is a strain developed at Virginia Tech and grown at the Heathsville farm of Billy Dawson. In the front room of the distillery is a photo of the distiller and the farmer, two men out standing in a field. The barley is delivered in 1-ton bags, then soaked in a vat beneath a sign that reads “5614 km to Loch Indaal” the Scottish water that laps against Islay – before being shoveled out onto a concrete floor and spread with a spatulate-fingered iron rake, dragged first in a spiral and then in Zenlike swirls, the combination of water and temperature urging the seeds to convert starch to sugar, to prepare to sprout and fulfill their destiny, as Wasmund says. But no. Instead they’re hoisted onto a perforated steel floor above a wood stove topped with smoldering cherry and apple wood, the smoke infusing the barley for hours before it is taken outside and ground in a mill powered by an old John Deere, its transmission faulty but its drive shaft well able to drive the augurs that grind the grain.

Wasmund then blends the ground barley with rye and yeast and water from the mountain-fed aquifer into a hot, sweet, smoky soup of grain he leaves to bubble in tanks, to turn from a johnnycake-looking slurry to something toasted and granular, bubbles spitting and foaming to the top, the air above it so thick with CO2 that it crowds out all of the oxygen.

Only then is it pumped into a traditional, onion-shaped, copper pot still, then poured into barrels with a special trap lid, through which he stuffs cheesecloth bags of toasted oak and applewood chips. For a year those chips will stay there, absorbing and releasing the whiskey. Then the whiskey will be moved into traditional barrels, put into a barrel heater and pulled out once a week to be rolled the length of the distillery as workers sing, to the tune of

Roll Out the Barrel:

Roll-ing hot barrels, Wasmund demonstrates.

Rolling hot barrels of fun.

Rolling the barrels … (“Here you have to push with your feet,” he interjects.)

Making Wasmund’s whiskey Number One …

Rolling hot barrels, it’s fun for you and for me!

Roll-ing hot barrels … at the Copper Fox Distillery!

And then you have to go down and touch the barrel and the malt room door at the same time so you don’t cheat, then turn around and come back.

“I’m management now, though, so I have to miss some of the rollings, which is too bad.”

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

The barrels sit and cool for a couple of days, then go back into the heater and then get rolled again, all in an effort to make a richer product in shorter time.

The bottles here are hand-filled, their openings then dipped into hot wax – “I think Mom has forgiven me for stealing her crockpot” – and twirled just so, to make a perfect swirl on the top, a C, as in Copper Fox.

“We’ve heard there’s another whiskey that uses red wax, but theirs looks drippy and sloppy, and we figured maybe that’s how they make their whiskey,” Wasmund says. “But we’re Virginians, so we do things properly.”

An hour and a half away, down roads rolling north and east between miles of stone and wooden fences, past paddocks and race tracks, in the mowed and manicured, mink and manure horse country northwest of D.C., is Purcellville. The commercial hub of western Loudoun County, it’s a popular lunch spot for visitors to area vineyards, and home to 8,000 souls and the Catoctin Creek Distillery, freshly moved into a brick building on Main Street that was once a bank and then housed a car dealership that showcased big-finned Buicks. The floor now is tiled with end cuts from the heart of a mesquite tree and polished to a rich shine. Floating clouds of the original ceiling tile hang over the curved bar and café tables of the tasting room, with its view through original sliding-glass doors to the working distillery, where chemical engineer Becky Harris and distiller Greg Moore tend a pair of shiny-copper German stills, everything about the process precise and consistent, which matters most when you’re making single-barrel whiskey.

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

The distillery was the dream of Becky’s husband, Scott Harris, after he slogged through a mind-numbing 15th revision of a PowerPoint slide that he knew no one was going to remember. For their first year and a half, he worked days at his government job and nights setting up and running the business. Then he started to telecommute, setting up a glide path from his stable, well-paid job at a defense contractor to working at the distillery full time. For the first 18 months Becky worked alone at the place, in an industrial strip next to car repair shops, fermenting the mash, running the still, finding the perfect time and temperature to separate off the heads – which are the toxic acetones and methyl alcohols that rise first off any mash, best suited for fingernail polish remover and auto fuel – seeking always the sweet heart of the run, the alcohol so pure and smooth it barely needs to be aged.

She learned where to stop in order to leave behind the harsh-tasting tails, those alcohols that are the last to distill off and whose flavor, she says, can get interesting only if they’re left long in a barrel. Her cuts, as they’re called, are judicious and conservative, based on temperature, volume and nose. “That’s really where the art meets the science,” she says, “because as the distiller I have to understand not only how things influence the

flavor of the raw spirits but how that flavor is translated after the aging process.”

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

Catoctin opened in 2009, and its Roundstone Rye is a young whiskey, aged less than two years. It’s the style that was popular right around Prohibition, which was the last time there was a legal distillery in Loudoun County.

They make the un-oaked, un-aged Mosby’s Spirit, too, which is like what Virginians were drinking around the time of the Civil War, except at Catoctin the cuts are precise, the liquor as pure as possible, the flavor like citrus and yellow cake, with the peppery finish that tells you it’s rye.

Their spirits are certified organic, and kosher, the heads used to clean the equipment, the tails re-distilled into gin, the mash given away to local farmers, who feed it to their cows.

And thus the cycle begins again.

photography by RICH-JOSEPH FACUN

Originally published in DISTINCTION, November 16, 2013