If the Shoe Fits

photography by KEITH LANPHER

In its halcyon days, the Craddock-Terry Shoe Company’s Southland Factory Annex in downtown Lynchburg roared and rattled with enormous leather belts that turned axles that turned smaller leather belts that turned the spinning wheels of sewing machines. There were days those belts snapped loose and whipped like lashes around the heads of the workers, days of 100-degree temperatures, relentless days of the cacophony of metal against metal as hundreds of mechanical arms advanced shoe leather while others lifted and lowered needles, in and out of the recent hide. The heat and noise and smell were crushing as women in long dresses bent over Singers, their hair bunned back to keep it out of flywheels, and men stood at the larger MacKays, sewing on soles.

“Shoe factories at the time sounded like hell,” says D.A. Saguto, an expert on the history of shoemaking whose credentials include being the shoemaker at Colonial Williamsburg and working as consulting shoe curator for the Smithsonian and Mount Vernon.

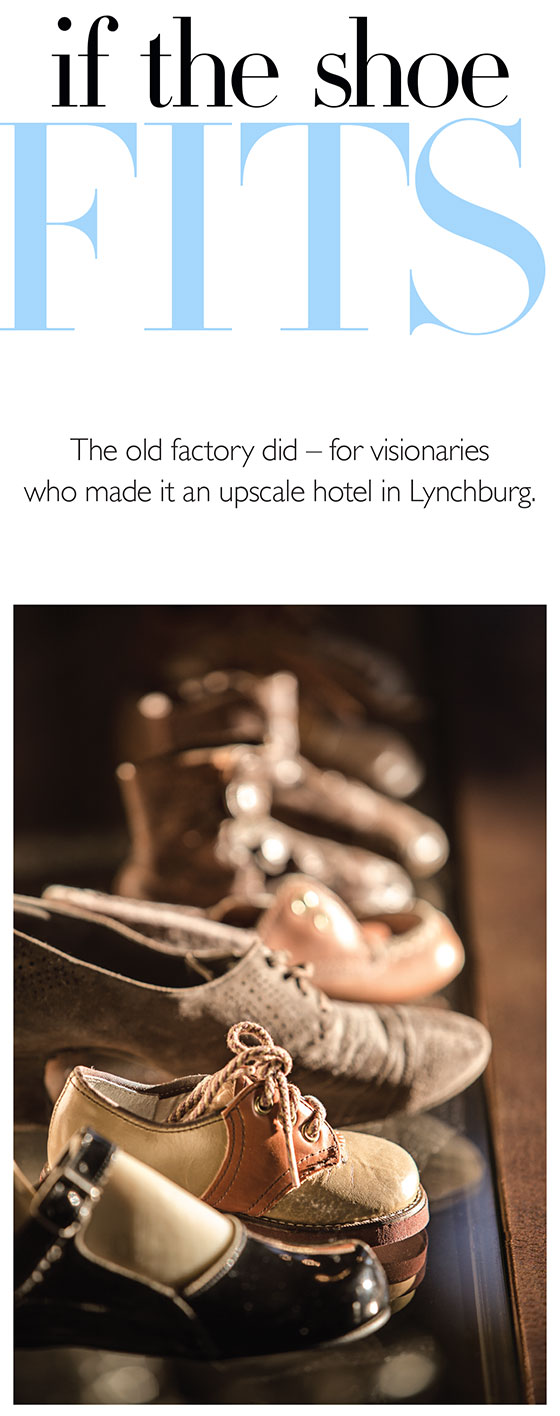

Today that same building is serene, the rooms quiet, the original beams and rolling metal doors standing as polished backdrops to beds piled high with pillows. The lobby at the Craddock Terry Hotel pays homage to the building’s heritage with baby shoes and men’s work boots, flats and sandals and colorful displays of women’s pumps. The hotel dog’s name is Buster Brown. You can walk him if you’d like.

photography by KEITH LANPHER

If you’re a regular, the reception staff will call you by name. They’ll ask about your mother’s surgery, your grandbaby’s ball game. If you tend to buy peanuts and a soda in the gift shop, you may find them waiting for you in your room, compliments of the hotel. Come with a group of men and you may be met in the lobby with chicken wings and growlers of fresh beer from the brewery and restaurant downstairs. A more genteel group may find Champagne and berries.

The guest rooms are along thick-pillared halls or up industrial stairways. On each bed is a replica of a shoeshine box. Set yours outside the door at night and in the morning it will contain a breakfast of fruit and Brie, and a fresh croissant. Set out your shoes and they’ll come back polished.

The main building is connected by a walkway to more guest rooms in a converted 1890s tobacco warehouse, its original architecture attributed to August Forsberg, an engineer for the Confederate Army. The walls are solid, the floors thick planks of pine. There are two restaurants – the high-end Shoemakers American Grille and the pizza-centric Waterstone – plus a small-batch brewery and a pair of conference rooms, one with views of the river and the other looking like it was hewn straight from the granite.

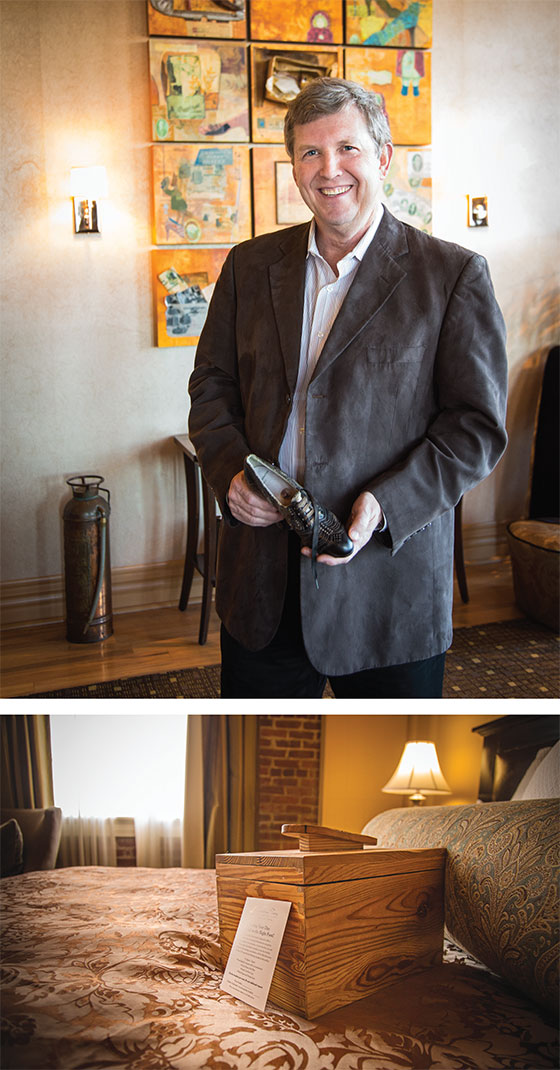

Hal Craddock, who had the vision to restore his forebears’ factory, and the last shoe it made.

photography by KEITH LANPHER

Hal Craddock, who had the vision to restore his forebears’ factory, and the last shoe it made.

But the road from what was to what is was steep and rocky.

The original shoe factory opened on the Lynchburg riverfront in 1888. Demand was steep, so in 1905 the company added an annex – the building that’s now the hotel. Other Craddock-Terry shoe factories sprouted in small towns throughout Virginia, Missouri and Ohio. The Lynchburg factory had a retail space the locals called the Shoe Room, and much of the town shopped there. Business faded during the Great Depression, then soared again as orders poured in for combat boots during World War II, eventually making Craddock-Terry the fifth-largest shoe company in the world. After the war the factories went back to shoes – and entire busloads of tourists were lured to the Shoe Room by billboards that featured 22-foot-tall red fiberglass pumps – but shoe manufacturing was increasingly moved offshore, and one by one the factories stuttered to a stop.

The giant shoes were carted to the bone yard behind the sign maker’s shop. Stores left downtown for the mod new strip malls a few miles away. Doctors and architects and lawyers followed. Restaurants closed. The downtown deteriorated and historic factory buildings and warehouses stood vacant.

But Hal Craddock had a dream.

Craddock, 64, is the great-grandson of John W. Craddock, one of the shoe company’s founding partners. He grew up in Lynchburg, left to study architecture at Virginia Tech, and spent two years in Brazil with the Peace Corps, then came home to partner with and eventually take over from an older architect, hoping all the while to help figure out how to revitalize the riverfront and downtown.

“I’d see all these beautiful old brick buildings and it was idiotic to me that everybody was moving away,” he says. “The stores, the residents, were moving to suburbs, everybody was driving around in cars, everything was starting to look the same. Downtown had all these beautiful old structures, and people were just ignoring them.”

So in 1980, he and two friends in the advertising and graphics business pooled their money to buy one. The one they chose was an 1899 Anheuser-Busch bottling plant just across the railroad tracks from the river and across the street from the shoe factory annex, Craddock’s family name still in faded paint on its bricks.

The former beer-bottling building was then owned by the Lynchburg Foundry, and Dick Gilliam, the man in charge of buildings for the company, wouldn’t sell it because it was full of casting molds for the iron parts the foundry made for giant earth-moving machines. Craddock and his friends decided they had to do something to get his attention, so one of the graphics guys created a mock front page of the local newspaper that included Gilliam’s photo and the headline “Dick Gilliam Sells Building to Young Entrepreneurs, Saves Riverfront.”

photography by KEITH LANPHER

“We put it on his desk on a Friday along with a $35 box of cigars with a big sign that said ‘BRIBE,’ ” Craddock says. “On Monday morning he sold us the building.”

The headline was more prescient than they could have guessed. Craddock and his partners used state historic tax credits and spent about half a million dollars to fix up the space before they could move in. But Craddock has what he calls The Vision Disease, and he kept looking at the decaying buildings across the street, imagining what they could become.

One night he stayed in the Brookstown Inn, a boutique hotel in an old textile mill in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He struck up a conversation with the manager and learned that the hotel’s primary business came not from weekend visitors to the historic district but from business travelers. The hotel staff set out wine and cheese every weeknight. They made customers check out in person so the staff could get to know them, and created relationships by scheduling the same people at the front desk every time they knew a repeat customer was coming.

Craddock was so intrigued that he begged the manager there to tour the two old buildings in Lynchburg, and that manager reinforced what Craddock already believed. The buildings were in a reviving downtown, there was the railroad, the picturesque James River and neighborhoods full of historic homes. “You should do this,” the manager said.

Next, Craddock hired a graduate student at Virginia Tech’s hospitality school to do a market study for him. The student’s opinion was that a boutique hotel would suffer but an upscale restaurant would thrive, because there wasn’t another one downtown.

Craddock asked the city to go after an economic development grant from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“If anyone else came in here and said they’re going to put in a boutique hotel and several restaurants, people would have said, ‘Are you crazy?’ ” says Marjette Upshur, Lynchburg’s director of economic development. “But Hal just comes and presents the case. He’s not trying to be some big slick developer; he just tells you the truth, good, bad and ugly.”

They got that first HUD grant, then a much larger HUD loan, but rehabbing the old buildings was going to take millions, so Craddock and his partners threw parties in the shell of the old building, wooing people for investments of $75,000 and $150,000 in exchange for shares in the project. Friends, family members, community leaders opted in.

Craddock drove up the hill to the old sign company and asked for one of the bright red fiberglass shoes that were rotting away behind the building. He didn’t have any money, he told the owner, but could give him a share in the company. The owner hoisted the 500-pound shoe and latched it onto the side of the proposed hotel.

Craddock wasn’t the only one with a vision for the downtown. The local Junior League was converting an old grocery warehouse into a children’s museum. A group of artists was creating a downtown artists’ loft.

And in the late ’90s Rachel Flynn, then-director of city planning, invited Charleston Mayor Joe Riley to town to talk about possibilities. Riley took pictures all over downtown Lynchburg and put on a slide show that showed downtown Charleston before and after its riverfront restoration. Then he showed the photos of Lynchburg, which looked just like the “before” photos of Charleston.

“Lynchburg can do this,” he told his audience. “It can be a smaller version of the success we had in Charleston.”

“That presentation changed everything,” Craddock says. “Everybody started paying attention to downtown.”

But then the planes hit the World Trade Center and banks didn’t want to hear about hotels and restaurants, so a real estate investment consultant told Craddock to forget about his plans for a hotel and restaurants – tell banks you have two beautiful old buildings with four guaranteed tenants. Never mind that the tenants were all Craddock and his friends in different forms.

Craddock had put seven years into making the dream come true. He had persuaded friends and family to risk their money alongside his, and now everything seemed lost. One night he told his wife, “I think we’re going to have to declare bankruptcy and lose all our money.” His eyes get misty as he remembers. “But that night I opened my computer and there’s a full prospectus from Wachovia Bank to develop the project.”

That was 2004, and it wasn’t over. The complicated deal took another year to coalesce. Then Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast and the price of building materials soared, forcing Craddock to have the project re-bid. The total had jumped a million dollars, but City Manager Kim Payne came through with city loans for almost all of it.

Construction moved forward.

photography by KEITH LANPHER

The tobacco warehouse had been used for pack-rat level storage – furniture, tires, an entire car – all of which had to be cleared by the former owner before the partners would take possession. Twenty-five hundred cubic feet of stuff, plus 10 tons of rock to cut out to make basement rooms for the hotel.

Once again, money ran out.

“Things got so bad that Wachovia sent the trench coat guys from Philadelphia to tell us we were in trouble,” Craddock says.

Then Wayne Martin, a cousin-in-law of partner Cliff Harrison, visited from his home in Spain and wanted a piece of the project. He could afford to buy in at the $75,000 level, but Craddock had to say no. He needed to save every available share for the person who could come in with the $1.2 million he needed to finish the job.

Martin went back to Spain. Two weeks later he called back – “How about a million-two?” Again Craddock’s eyes get misty as he tells the story.

“That hotel feels the way it does,” he says, “because of all of the people involved.”

One of them is his business partner, Lynn Cunningham, who selected local companies for the furniture, the leather, making each room work despite the quirks of the floor plan. There are rooms with high ceilings and bolt-studded beams, and lower-level rooms with walls carved out of the original rock. There are jetted tubs and minivan-sized glass showers, tall windows and plush beds.

Around the hotel – and some say because of it – there are loft apartments and restaurants and a city park with festivals all summer. The city is now building the Lower Bluffwalk Promenade, designed to be like the High Line in New York or the riverfront walkway in downtown Charleston, which will run for five blocks along the river from Amazement Square — the children’s museum that now attracts 90,000 visitors a year— to the balcony of Shoemakers, and Craddock is eyeing neighboring buildings for an expansion that would include 50 more rooms and a spa.

“Hal’s like an evangelist,” says Upshur, the economic development director. “You really need people to show you how things could be, and here that was Hal.” The property went from paying $610 in property taxes when Craddock bought it in 2003 to paying $548,000 in lodging, meals, sales and property taxes in 2013, she says.

“Downtown’s where your history is. It’s where your personality is,” she says. “Nobody ever moved to a town because it had a strip mall, so our downtown is vital.”

“In this world we tend to want to know exactly how things are going to work out,” she continues, “but sometimes you just have to take a leap of faith.”

That sounds like something Hal Craddock would say.

The hotel – wearing a 500-pound shoe rescued from a trash heap – now is a linchpin of

Lynchburg’s reviving downtown, its annual tax contribution soaring to $548,000 from $610.

Originally published in DISTINCTION, February 16, 2014