Brian Boggs, Master of The Chair

A lifetime of tinkering has led Brian Boggs to create a line of innovative woodworking tools, and some of the world’s finest chairs.

“I’ve always been kind of intense,” Boggs says, “but if I’m going to do something, especially for this long, I want to know it inside and out.”

Brian Boggs made what some people called the perfect chair. A ladder-back with a woven hickory bark seat, it was beautiful, durable, lightweight, and, most important, comfortable no matter your body type. He named it the Berea Chair, after Berea, Kentucky, where he briefly went to college, had a family, honed his craft.

He’d innovated the backs and the legs, taking a 200-year-old design that farmers had made in barns and Shakers had made in simple wood shops and “he did something to the seat and a lot of something to the back and performed a simple trick that rotated the back legs,” says Gary Rogowski, who runs the Northwest Woodworking Studio, a furniture-making school in Portland, Oregon. Boggs tinkered with this chair until it was as beautiful and sturdy and comfortable as it could be, until it was the kind of chair that other chair makers, including Rogowski, bought for their own homes. When it was done, Boggs loved it. “It’s the best chair you can make!” he’d tell people at craft fairs. And plenty of others agreed.

“In my judgment Brian developed a chair that is in some overall way the finest chair I’ve come upon,” says Peter Korn, director of the Center for Furniture Craftsmanship in Maine, and a habitually tough critic. “It’s comfortable, durable, beautiful, light weight. From a woodworker’s point of view, it makes incredibly good use of wood as a material to get the most out of it in terms of natural properties of strength.”

Over time, Boggs’ muscle memory could turn out one of these chairs in 10 hours flat. To accomplish this, he’d even created a collection of his own tools. He modified a curved spokeshave to weigh just right in the hand, which sped the shaping of the chair’s legs and spindles. He’d also redesigned a shave horse—a common tool whose design has remained basically the same for centuries—so that it adapted to any artisan’s body, thereby alleviating his own aching back. For his first 300 chairs he hadn’t plugged in a power tool. When he finally got an electric router, he turned it on, then promptly put it back in the box. “It seemed like someone screaming at me,” he says.

But because he’s Brian Boggs, he took the router out again, curious about what he could do with it—what designs and efficiencies he could create, and what chairs he could make if he could accept a newer technology. He also redesigned the router over and over until it could create the locking tapered joints that opened up the household chair to a world of revolutionary possibilities. “It’s prestidigitation, almost like magic,” says Rogowski, a discriminating critic in his own right. “You’re going ‘what the hell is that?’ ‘Who comes up with that?,’ because that’s crazy stuff. He just blows me away, and he just continues to do it.”

But then Boggs was done. In the spring of 2018, he quit making the Berea chair. “I knew in my gut that I was overdue for the next step,” he says. “It’s an ancient idea of a chair design. And they’re so good. But I can’t fix that form, so I learned how to make a much, much better chair.”

THE REWARDS OF RISK

At this point, Boggs hadn’t made any improvements in his Berea chair since he splayed the legs back in 2000. He was tired of being restricted by a small set of tools, a log of wood, and some hickory bark. “Each addition of a tool,” he says, “added a color to my palate or a degree to my bandwidth in thinking.” Now he wanted to combine his skills, his knowledge of wood, and his new techniques to create something even better.

Besides, the Berea chair was bugging him. The seat had no specific shape. The rationales behind the time-honored way of making it had less to do with function and durability and more with the technological limitations of the time. “Those chairs evolved out of a very primitive barn, a lathe, a chisel and very little else,” he says. “And access to trees. That’s beautiful and I love that, but it’s very limiting. I had to leave it. It seems in some ways less genuine every year to continue making this chair. It was who I was, not who I am.”

There was also a limit on how much money Boggs could make on a peasant chair, and he wanted to expand from vow-of-poverty chair-making to building a business. By this time, Boggs had moved back to his hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, and married his second wife—Melanie Boggs, his now-business partner. They soon opened a 10,000-square-foot shop, called Brian Boggs Chairmakers, on the edge of Asheville’s River Arts District. Here, looking out over the Blue Ridge Mountains, 11 employees (including the Boggses) turn out approximately 200 pieces a year.

In 2018, Boggs took a risk. He told the 30 customers on his waiting list that he was going to create a new chair, a better chair, and they trusted him. They waited. He thought it would take three months; it took 24. For two years, Boggs moved lines and shapes and made scale models and tried options and wasted materials, his business struggling. He could see the curves he wanted, the back. Those answers were straightforward, he says, but they weren’t easy to create. And the perfect seat remained a challenge.

THE POWER OF A PENCIL

Boggs is intense. He’ll admit it, and his former employees will, too. The level of precision he demands is such that if a human hair can slide into a joint, it’s too loose. He talks in fully thought-out paragraphs that describe, in detail, how a tree’s growth rings and rays and pores work in concert to make the strongest leg, the sturdiest joint. The classic system of mortis and tenon—the hole-and-peg method that allows woodworkers to attach furniture parts without nails or screws, and that has survived longer than this nation—was not good enough for Boggs. Among other things, it squishes all the glue to the bottom of the hole. So Boggs tried out a tapered tenon, and found that the taper allows the tenon to slide almost all the way in before it tightens into the mortis. This keeps all of the joint’s surfaces coated with glue; it also helped Boggs rethink how a chair can be made.

Unlike most furniture designers, who use CAD (computer-assisted design) programs to create their products, when Boggs set out to re-invent the chair he started with pencil and paper. “It’s like talking to myself,” he says. “It’s an invitation for ideas to come in.” Plus, Boggs feared that a CAD program would drown him in a learning a process—without taking into account his intimate knowledge of wood. He wanted to tinker with the wood itself; make actual 3D models that he could hold in his hands, turn this way and that, examine from every direction. It’s in the quiet of that tinkering that he had his ah-ha! moments.

“I don’t think the ideas that are expressed in my chair designs are ones I’ve generated,” he says. “They’re ones I’ve been gifted. Really good ideas come to those who are honestly asking for them and open to receiving them. I think we’re in a bath of ideas all of the time, it’s like the water a fish is in. The fish doesn’t know it’s there. They’re not thinking about the water, they just know how to move in it. I hold a belief that in this infinite universe we swim around in, there is truly an infinite number of ideas and an infinite number of ways to do things. As soon as you think it’s all been done, you’re done. If you think there are no more ideas to play with, you’ve stopped asking them to visit you.”

CRAFTSMANSHIP AS STORYTELLING

Boggs was in second grade in Weaverville, just north of Asheville, when his teacher gave the students a pile of triangles and circles and told them to create a picture. His so impressed her that she told his mom to enroll him in art classes. Within the first year he moved from the kids’ classes to the adults. “The kids’ classes were for entertainment, not teaching art skills,” he says, “and I was ready for skills.”

He was 8. Over the following years he toyed with pottery, then took up drawing and oil painting, but the two-dimensional format didn’t work for him. “I had only been trained to represent what I was seeing, not tell a story or conceive something that isn’t,” he says. “I couldn’t bring something into existence, and I got extremely frustrated with my ability to feel something but not paint it.”

Soon after, Boggs stumbled across “The Fine Art of Cabinet Making,” by James Krenov, the mid-20th-century woodworker credited with helping to revive the art of handmade furniture, and the clean, natural aesthetic he championed. The book cracked him open. He’d never seen furniture as art. A chair was a place to sit, a cabinet a place to store socks. He started playing with some simple hand-planes, trying to feel what it was like to create art using wood. Then he found “Make a Chair from a Tree,” by John Alexander (who later transitioned to become Jennie Alexander). Where Krenov used a full woodworking shop, Alexander had a sledgehammer and a small box of hand tools; Alexander would hike out into the woods, cut down an oak or a maple, and turn it into a chair.

By the time Boggs was in his early 20s he had followed a girlfriend to Berea College in Kentucky, where he dropped out after a year. Boggs knew what he wanted to do and he didn’t need a college degree to do it. He talked with woodworkers, read what he could find, made a lot of mistakes. At first, he didn’t have a chisel, let alone a spokeshave; he carved with a sharpened screwdriver and made holes with an old hand-drill. Boggs’ experimentation, along with the books and his conversations, shaped how he viewed wood: as a bundle of fibers that can be pulled apart and put back together in a different shape. “If you’ll look at any of my chairs, and let your eye take a drive down the curve,” he says, “you’ll see that the grain follows that curve almost exactly, in a very specific orientation.”

“I JUST STARTED STARING AT IT”

When Boggs first began playing with ideas for the chair of his dreams, he tried to create a “splayed, tapered, curved torsion box.” In other words, splaying the chair’s legs made room for a person’s leg movement without making the whole chair wider (which would make it both heavy and difficult to get into if it were flanked by other chairs); tapering the seat created elegance; and turning it into a torsion box brought strength without excessive weight (picture an airplane wing, or a hollow-core door; both are torsion boxes). To make the seat, Boggs tried covering a frame of sturdy oak with a thin veneer of walnut, but it wasn’t stiff enough in the center to withstand a clamp. And there was no way to seal it so the glue could properly dry.

“That’s the point where I just started staring at it,” he says. Undaunted, Boggs kept making chairs. While strong, with some beautiful lines, the chairs were heavy and ridiculously time-consuming. Parts that weren’t quite right started to pile up. “It was costing us out the wazoo,” he says. In the end only six got close enough to his standards to be sold.

After months of failed experiments, an idea bubbled up: Why not use a fabric composite to strengthen the chair’s hollow shell? “I kept running that vision through my head but I wasn’t sure what it was, so I just took a grinder to one of the seats I didn’t like and ground the bottom off to help me think through or see what was kind of incubating there.”

To feed the incubation, Boggs went back to making models, again by hand, slowing the process so that ideas could develop. He was doing something never done before, so he couldn’t consult experts—or even YouTube. He had to try and fail and try and fail. He started by creating a silicon mold. Then he turned to his 1937 band saw, refining his skills to the point where he could make two symmetrical curved parts that fit together perfectly.

“A UNIFIED PLANT IN THE SHAPE OF A CHAIR”

To find the right composite for his chair seats, Boggs at first tried fiberglass and carbon fiber, but he found that both materials ripped up his tools and sent dangerous filaments into the air. So, in search of something more natural, he Googled and learned that the strongest plant fiber humans cultivate is linen. Much like carbon fiber, fiberglass, or Kevlar, a sheet of linen can conform to anything. It doesn’t move in response to humidity, like wood does, and it’s strong and stable.

After some experiments, Boggs discovered what seemed like the ideal process: spread epoxy on a silicon mold, cover it with a layer of linen fibers, top that with a thin piece of veneer, flip the mold and repeat, then put it all into a vacuum press. Once Boggs figured that out, he realized he could use a sheet of cherry that’s no more than an eighteenth of an inch thick, and still make an unusually strong seat. The result, as he puts it, is “a unified plant in the shape of a chair.”

When Boggs finally unveiled his new chair, in 2019, his customers loved it, and the Cio (pronounced Chee-oh) was born. The chair is light, it’s strong, it’s elegant. And it is incredibly comfortable.

In 2019, the Cio won The Good Design Award from the Chicago Athaneaum: Museum of Architecture and Design and the European Centre for Architecture Art Design and Urban Studies—one of the oldest award programs for design excellence in the world. The win came out of a submission spree that Melanie embarked upon, in 2016, after Boggs’ first international contest. Called the “A Design Awards,” the competition celebrated an “exemplary level of sublimity in design,” and it led to a trip to Italy for both Brian and Melanie. Boggs’ entry that year was an outdoor swing called the Sunniva Deluxe; it was designed to hang from its own framework, so those who sit in it feel like they’re floating, with no chain or rope to impede their view. When the swing won its category, Melanie thought the whole experience was so much fun she decided to look for more competitions. Later that year, Boggs’ Grand Lily Arm Chair won first in its category in the Good Design Awards. A year later, in 2017, Boggs won again with his Sculpted Fanback Arm Chair—a design marked by floating arms and a latticed, spine-hugging back. At this point, the Boggses have entered four international competitions and won all four. Boggs had finally built the viable business he was after. Today, his chairs typically sell for between $1,900 and around $4,000, with some of his rocking chairs costing more than $6,000 apiece.

THE SPIRIT OF WOOD

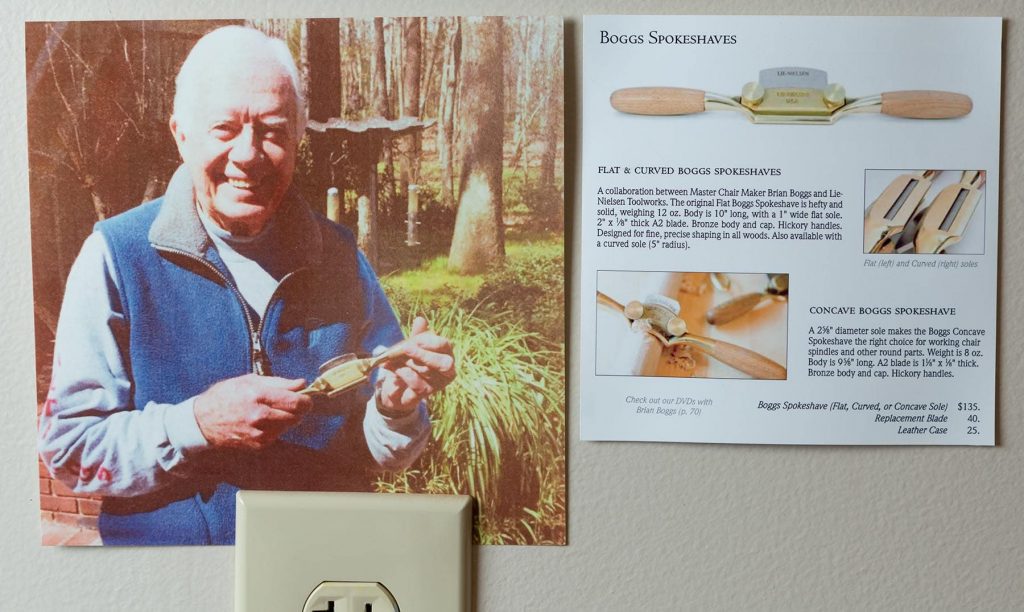

Boggs began making his own woodworking tools, which included the curved spokeshave, in 1983. Ultimately manufactured by Lie-Nielsen, the Rolls Royce of woodworker’s tools, the Boggs spokeshave is now sold around the world. On one wall in Boggs’ shop, there’s a framed cover of Fine Woodworking magazine that shows a grinning Jimmy Carter, proudly holding up a Boggs spokeshave, which the magazine gave him for participating in a story. “When Brian sets out to do something he redesigns the tools,” says Rogowski. “He’s a remarkable engineer. It’s demoralizing.”

Why go to the trouble of designing a new spokeshave, or a new router, or any other woodworking tool when perfectly good ones have existed for generations? For Boggs, it’s because the tools you have define what you can make. “Just like your ability to think has a lot to do with your vocabulary,” he says. “If you don’t have the vocabulary to say something, the thought doesn’t come together as well. And if you can’t speak the language in the country you’re in, it’s hard to express your thoughts. In woodworking, the infrastructure of the shop creates the language of your work.”

Before speaking a tool’s language, woodworkers of Boggs’ caliber teach themselves to study the language of the wood. Which growth rings, for example, should run in which direction to properly connect to other parts? What moisture content is best for a joint? Furniture makers who care about these questions tend to keep their tools simple, in order to improve their chances of feeling the answers with their own hands. This in turn helps them make those answers palpable for anyone who buys their tables and chairs.

“It’s not worth killing a tree just to get a customer’s butt 18 inches off the floor,” Boggs says. “But if we can make them more conscious of what is around them, we inspire them to wake up. Our products are not simply wooden. The wood in a chair is like the ink on the page of an inspiring poem. It is the spirit, imagination, inspiration, and motivation conveyed in the making of a thing or the writing of a poem that makes anything worthwhile, not so much the material thing itself.”

“A DIFFERENT KIND OF BEING QUIET”

Boggs won’t entirely dismiss new technology; he believes it can help artisans rethink and improve their work—as long as they don’t let it go too far. “We don’t have to stay in a hand-chiseled mindset,” he says. “We can go with a CNC (computer numerical control) mindset, we can go with robotics, but we have a 4,000-year collective wisdom on what works, on how trees respond to joinery and how to put plant parts together so they stay together. We’re throwing it away as we get drunk on technology.”

In the meantime, Boggs sees plenty of possibilities in the comparatively low-tech path he has pursued. “The stability of the material, and the ability to design super structures that are incredibly light and amazingly strong for their dimension, creates some pretty damn seductive design opportunities,” Boggs says. “We’re able to support wooden forms in a way that changes how we can think about design,” he says, “and that is flipping exciting.”

With Boggs, the ideas seem to keep on coming. “It’s not that I’m becoming more creative,” he says. “I’m just improving my landing pad so that ideas find me easier. It’s a different kind of being quiet that allows designs to come in and you just get the hell out of the way.”

Michael Oppenheim is a professional freelance photographer based in Asheville, N.C.