Eire in the Eye

Norfolk photographer Glen McClure has spent two decades capturing stark, moody images from Ireland

The Kilmeena causeway in County Mayo, Ireland, was narrow, and the gusting wind threatened to pick up the tiny rental car and toss it into the icy water below. But Glen McClure was chasing the light.

The photographer considered his options. Inside, the car was warm and dry. Outside, the sky was spitting cold rain – and a dog barked viciously.

McClure didn’t want to wreck the car, he didn’t want to be blown off the causeway and drown, and he didn’t want to be attacked by an angry mongrel. But that light! If he could capture it, conveying its beauty and drama and moodiness, the risks would be worth it.

The dog, it turned out, was small and friendly. Persistent, too. An impromptu game of fetch ensued.

As McClure set up his tripod, “I looked down at this little guy and he’s brought a rock, and he put it on my shoe.” So McClure threw it and returned to framing his shot. Then the dog ran back and set the rock on Norfolk photographer his shoe again. McClure threw it once more. Wiped the rain off his lens. Framed another photo. Threw the rock again. Wiped the lens.

For 20 years, McClure has returned to Ireland, tripod balanced on his shoulder, to hike over craggy rocks and follow the light. The journey has taken him down narrow roads, and into villages, and high atop bluffs. He shoots whatever catches his eye, overcoming obstacles large and sometimes charmingly small. The wind changes, the clouds skitter, the dog fetches. Mc Clure’s shutter clicks.

The wild weather appeals to McClure’s Scot-Irish blood and to his Ansel Adams-like eye. Twice the wind has stolen his tripod and camera – once tossing it 25 yards into a bog, once throwing it onto the rocks.

“It took me years to figure out why I kept wanting to go back,” he says of Ireland. “It was the skies and the constantly changing drama and shooting in the middle of the rain and the hail and somehow making it work. You know, it’s just all fun!”

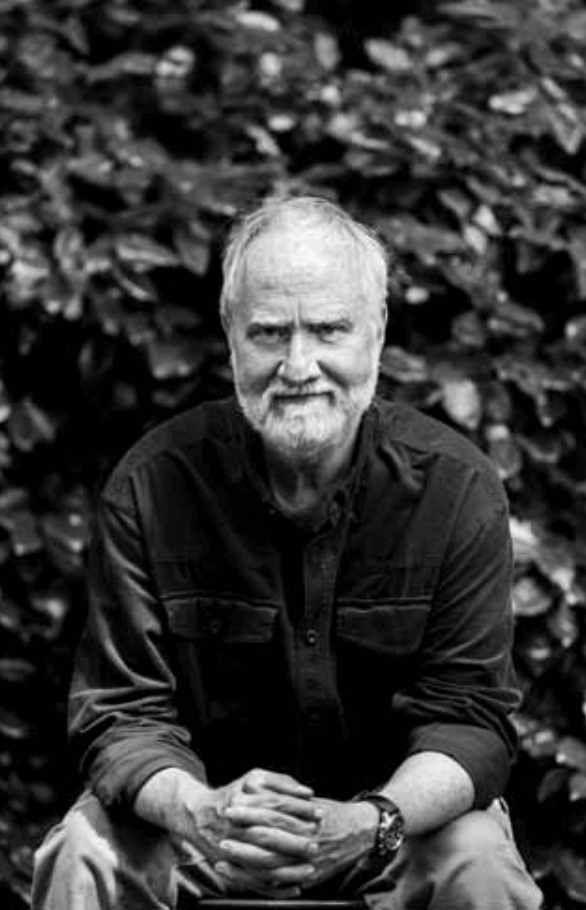

McClure, 67, worked for decades as a commercial photographer. Then in 1998 he set up a mobile studio outside his office on Colonial Avenue in Norfolk and took portraits of the people passing by. That led to a show at the former Contemporary Art Center of Virginia (now the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art) in Virginia Beach, which led to a show at the Vir ginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond.

In turn, his VMFA ties led to projects in which McClure captured portraits of Virginians across the state.

His series on shipyard workers was shown at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, the Peninsula Fine Arts Center in Newport News, the Charles H. Taylor Visual Arts Center in Hampton and the Portsmouth Art & Cultural Center.

“Glen has tremendous empathy for his subjects,” says Jeffrey Allison, the VMFA’s director of statewide programs and a former professor of photography. “You can’t make a wonderful photograph of someone and capture a tiny bit of their soul in that image if they don’t trust you.”

McClure approaches the world with curiosity and fondness, and more than a little glee. One time in Ireland, he and his wife, Marshall, who designs many of his books, were drinking tea at The Beehive coffee and craft shop on Achill Island when a woman who ran the place asked if they’d be back for the next day’s famous St. Patrick’s Day parade. “It’s just the pipe bands,” the proprietor said. “And people who moved over to New York and Chicago, they all come back for this.”

The next morning was cold and rainy, but the Mc Clures drove back. On the way they picked up two men, wearing what looked like Shriners hats, as they walked along the road. “So these two lads hop in the car and they’re about my age,” McClure says. “And they take us right to this hotel, where there’s a huge crowd. Everybody’s going inside and having hot whiskeys and beers before the start of the parade.”

The morning had begun with a lonely drummer marching through town at sunrise, to wake everyone. People poured into the local bar, then streamed across to the church. By the time the McClures arrived, the bar was stacked with emptied glasses, and the McClures tossed back some hot whiskeys themselves.

“All of the sudden the music starts up, and it’s a sound like none you’ve ever heard in your life,” McClure says. “It was like another world.”

By that time the rain had turned to hail. Gusty winds tore at skirts and kilts, and pinkened puffed-out cheeks. McClure started shooting as the local band led the parade to the next town, where that town’s band took over. At each place the players would stream into the bar, come back out and march to the next village. The procession went on all day.

McClure has returned so many times that locals recognize him. Some have since passed away, and their

families have displayed McClure’s portraits alongside the caskets. For him, it’s an honor.

“If you look closely, every fiber, every callous, every wrinkle, every line – it’s all there,” Seth Feman, curator of photography at the Chrysler Museum, says of McClure’s work. “It’s a kind of adoration. He really admires these things we don’t attend to very often.”

On another visit to western Ireland, the McClures had time to kill before their flight out, so the innkeeper recommended a particularly beautiful drive. It was a lovely day – 60 degrees and sunny, not a cloud in the

sky – yet McClure was grumbling. He isn’t interested in picture-postcard days. But he was 3,000 miles from

home, so he took a few photos.

He and his wife stopped at a local tea shop, and then they noticed a crowd outside the window, running to get out of the suddenly stormy weather. McClure grabbed his gear and started shooting. “The landscape of Ireland changes every single moment,” the VMFA’s Allison says. “It’s the most extraordinary light and landscape, between the ocean

and the woods, and Glen is brilliant at reading the the light. I think his soul opens up and he becomes one with that environment and is able to interpret it in a way few people can do.”

It’s McClure’s interpretations that make his photographs stand out. His eye, yes, in finding the photo, but also the old-school darkroom techniques he has brought into his digital darkroom. Like Adams, his photographs are not limited to what a viewer might see from the same place.

“I spend an awful lot of time working on my images in post-production,” McClure says. “I call them impressions or interpretations, because I’m not trying to totally just make a postcard of what the scene looks like. I’m trying to put my emotion, my feelings into all my images.”

Thus the skies may be darker than in real life, the light breaking through the clouds brighter, as he conveys the sense and the drama of what he sees. At the VMFA, which is currently exhibiting Adams’ work, Allison notes that the famous photographer’s finished images also don’t look exactly like the scenes as initially captured. Adams, too, manipulated his photos in the dark room.

“Glen is very much in that tradition,” Allison says. “He is trying to present a feeling, not just the look of

a place.”

McClure’s newest book, his ninth, is another chance to transport viewers to Ireland, to show the world what he sees on the moody island, to tell people’s stories. There are black-and-white shots of stone house and skies and crags, and color portraits of bagpipe players young and old.

One day, he and his wife were at a beautiful beach, with him complaining again about how perfect it all was. “Glen, just let your eyes do the work,” Marshall said suddenly. “Just look.”

The sky was boring, so McClure glanced down and started shooting reflections in pools of water. He created some gems.

“That kind of changed a lot of things for me,” he says. “Don’t go expecting what you’re supposed to see.