Why the city of Staunton is an overlooked Victorian marvel in the Blue Ridge

Back when Virginia was vast, before West Virginia split off during the unpleasantness between the states, there was a bustling town at a curve on the rail line. Settlers would cross the Blue Ridge Mountains and there it was – Staunton, the seat of Augusta County, a hubbub of commerce and culture.

It had colleges, finishing schools, a military academy, vaudeville houses, an opera and hotels. Water from surrounding mountain ridges converged and rushed through the town, pushing industrial wheels and powering steam engines that ground wheat into flour and planed trees into planks of pricey Appalachian hardwood. Thirty-five trains a day clattered through Staunton, loading straight into warehouses along Middlebrook Avenue, a part of town locals call the Wharf.

Over time, though, paint peeled and pigeons roosted.

The area became littered with whiskey bottles and newspapers deposited by the wind.

Plans were made for what Frank Strassler, executive director of the Historic Staunton Foundation, calls a four-lane highway to nowhere, to carry people out of town as quickly as possible. But the foundation fought and the community rallied, and now those buildings have been renovated into luxury condos. There’s a diner, a lawyer’s office, a knitting shop. An old hotel with bats in its belfry became the area historical society.

The White Star flour mill is being transformed into a boutique hotel.

Those efforts helped Staunton (pronounced STANton), with one of the few downtowns in the South not burned during the Civil War, become the first town in Virginia to receive the Great American Main Street award from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

The whole of Staunton is an architectural marvel, with Victorian flourishes next to Spanish tiles next to Italianate archways. The downtown was designed primarily by T.J. Collins and his son, Sam, architects with a world of ideas and customers with imagination and fat pockets. You can see their work still if you step back and look up, above the plate glass and siding of charming shops selling everything from antique clocks to tchotchkes to scented candles and handmade jewelry.

Better still, take one of the free architectural tours offered every Saturday in season.

“During the Victorian era, everything was fanciful and people dreamed big, with an eclectic explosion of architecture all over,” says Kathy Moore, a local publicist, “but in Staunton, during this era of prosperity, noted architect T.J. Collins drew upon the rest of the world for inspiration with revivals of historic styles.” The Collins imprint extends to the Thornrose Cemetery, a 12-acre, parklike expanse of arches and angels.

(Stop first at Newtown Baking for a bear claw to enjoy as you wander.) The section called Fort Stonewall Jackson, dedicated to 1,700 Confederate dead buried there, is crowned by an Italian marble statue of a Confederate infantryman towering 22 feet in the air.

The walk takes you past the Once Upon a Time Clock Shop, where grandfathers bong and French ceramic mantel clocks tick and chime, and people from around the world send their clocks for repair. It takes you past the former YMCA, where the original Putnam parlor organ was invented, and past Huss & Dalton Guitar Co., whose instruments are internationally famous.

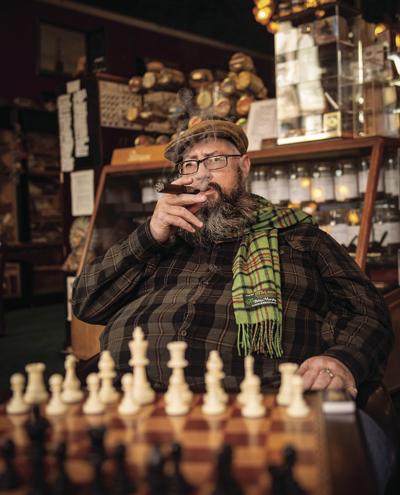

There’s the Beverley Cigar Store, whose gold lettering advertises “Fine Accoutrements for the Gentleman” and whose air smells of tobacco and leather. Up the hill is the Trinity Church, site of the town’s first formal graveyard and home now to an ornate collection of Tiffany glass windows, best seen from the serenity of the arched nave.

Instead of speeding out of town on that highway to nowhere, creative people have continued to arrive.

Twenty years ago, Carsten Schmidt started the Staunton Music Festival, which now brings 8,000 classical music fans each summer to this town of fewer than 25,000.

Churches and theaters – nearly every public space – swell during August with full philharmonic orchestras, chamber music quartets and operatic sopranos. The Baroque, Renaissance and Medieval programs are performed on period instruments.

One of the primary draws here, though, is the American Shakespeare Center, where a professional troupe performs year-round in a re-creation of the original Blackfriars Playhouse. Audience members convene at the on-stage bar or sit on one of the gallant stools amidst the players, addressed often by those actors in mid-performance.

The interior of the theater is wood, some of it painted in the fancy Victorian style to look like marble. Huge faux-candle chandeliers light a stage that juts into the audience, as was done in Shakespeare’s time. Backstage – which you can tour – hangs a clear plastic shoe holder with pockets marked for pitch pipes, drumsticks, recorders and slide whistles, plus valve oil, and mandolin, lute and ukulele strings. An upright bass leans in a corner, stage furniture is stuffed like Jenga blocks in every possible space. Actors declaim in Shakespearean English, swapping roles and sometimes genders, and singing bawdy songs during the breaks. The license plate on a car out front reads Bard4LF and the actors can be seen trodding the sidewalk to the restored Stonewall Jackson Hotel next door.

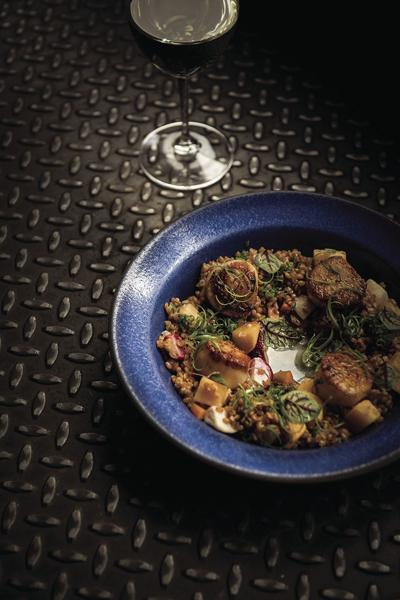

Staunton is a foodie town, with restaurants offering inventive tacos, traditional Thai, Salvadoran pupusas, Vietnamese phô and Indian vindaloos.

James Beard-nominated chef Ian Boden, owner of the 26-seat The Shack, culls from surrounding farms to whip up schmaltz focaccia and ricotta casoncelli, with brown butter and pecans.

Around the corner is Zynodoa, which bills itself as upscale Southern cuisine and serves molasses-brined chicken breast and bruleed cast-iron cornbread.

At the tiny storefront eatery LUNdCH, chef Mike Lund, who honed his skills at the five-star Inn at Little Washington, whips up prosciutto-wrapped asparagus and veggie bowls of whatever is in season. On Thursday nights people queue for a hot dinner to go.

There are wineries, distilleries and breweries in close proximity, so many that the visitors’ bureau has created a beer passport. Get it stamped at any six breweries and you’ll win a T-shirt.

Half a mile from downtown is the former Western Lunatic Asylum, now the Blackburn Inn, designed by Thomas Blackburn, who trained under Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s influence shines in the Ionic columns and neoclassic design.

Inside, the rooms are spare, the fixtures industrial chic, the floors stripped-down wood, their knotholes showing. The doors are thick with paint, the slot windows that caretakers would swing open to check on patients stuck shut with age. A set of stairs is worn to a sag in the center from generations of mentally ill patients trudging up and down, to and from meals and treatments and their fresh air time out on the lawn.

At the time it was thought that mountain air and outdoor exercise were curative, so there were spiral stairways to a rooftop walkway that provided the best view of the mountains in the whole town. Later, restraints, electroshock therapy and lobotomies became common and the rooftop walkway was closed. The lawns are still lush and sweeping, though, towered over by oaks that line the drive.

Staunton was quick to adopt the automobile, beginning with what is now the showroom and shop of Bruce Elder’s Antique and Classic Automobiles, with an early and still-working electric car elevator that carries cars to the top-floor body shop. The ground floor is a museum of classics, some of them loaned out to be used in movies.

Up the street is the free Camera Heritage Museum, which traces the history of photography through its collection of nearly 2,000 cameras. The fire station displays the last surviving 1911 Robinson motorized fire engine. Just on the edge of town is the Frontier Culture Museum, where buildings from the immigrants who settled this land – by choice or by enslavement – have been transported and rebuilt. You can stoop into smoky whitewashed homes moved from England, Germany and Ireland, or into the thatched-roof mud huts of West Africa. Docents run smithies or care for Old World chickens, while children run behind rolling hoops.

One of the joys of Staunton is its walkability, but if you do want to hop in your car, it’s a quick drive to Skyline Drive and to Shenandoah National Park, with trails and waterfalls, wildlife and scenic overlooks. Then — if it’s a Monday — return to Gypsy Hill Park, with its duck pond and bandstand, to hear The Stonewall Brigade Band, the oldest continuous community band in the nation, for a summer concert of Sousa marches and sacred songs, Broadway melodies and the national anthem. Bring a chair and a picnic.

Staunton, just a three-hour drive from Tidewater, blends history and forward-thinking creativity. Immerse yourself in architecture, learn about the people who settled the Shenandoah Valley, or just drink beer and hike.